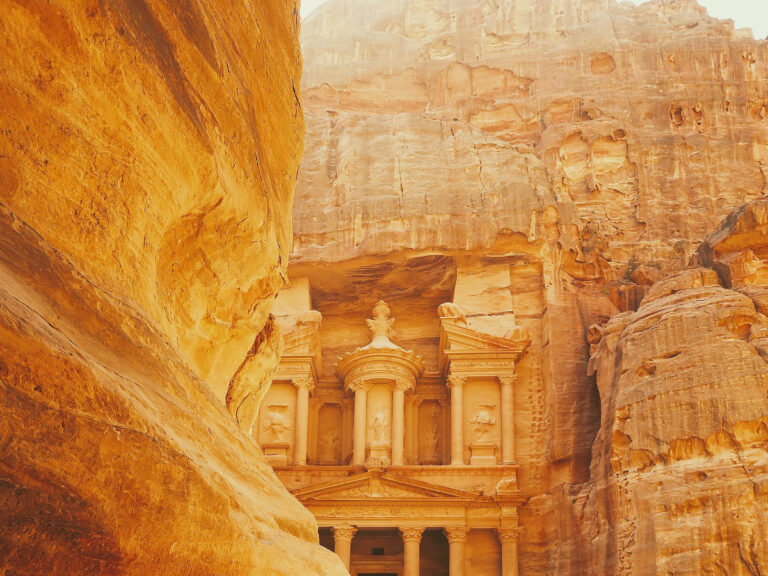

Photo by Katy Morikawa

Audio

Or find the audio wherever you get your podcasts.

I keep getting questions from people asking me, “What is the imaginal?” or “What do you mean when you say that?”

It’s a good and important question, and I’ll start with the vague notion I’ve been using, which goes something like this: It is an entryway into the invisible realms of Truth, into the numinous or transpersonal realms. But unlike visionary or prophetic access to these realms, it is malleable to a certain extent. It can be shaped by our creativity and imagination. We do not have unlimited free-reign with our creativity here, for even as we shape it, it affects us, it transmits its truths to us, it informs our art. With the imaginal, we do not simply access life’s familiar realities–those which can be had through traditional knowledge, lived experience or insight. Rather, the imaginal taps into a higher order of reality, but softly. Where the visionary stabs with shocking brilliance, the imaginal hints and reveals subtly, like a cat at the curtain. Where the prophet calls back from its farther shores, the imaginal beckons. I still do not know my own name for that country, but Tolkein called it the realm of faerie and Jung the collective unconscious, home of the archetypes. To access the imaginal realm (as a place) and to partake of the imaginal process (as a type of work), we must open the imaginal eye. This is a process with both psychic and heart-centered dimensions. I’ll note, because we’ve become so dissociated from the heart in modern life, that the heart’s vision or knowing is actually closely related to conscience–the little voice inside that knows what is right.

While imaginal work is not widely practiced or known in contemporary life, artists do seem to refer to it when they talk about working with the Muse. And in fact, my mother (that’s her in the photo above, isn’t she beautiful?) came alive as I began writing about the imaginal at the start of the year–as I knew she would, because I witnessed her discover the Muse while working on a video project in 2016. Her words near the end of that piece speak more directly from the heart than all of my thousands: “When I stumble into the flow of creative mind, I feel connected to a great living essence that informs, relates, contributes, supports, nourishes my work. I appear to be working alone, but I am not alone.” Interestingly, visionaries and inventors speak of inspiration in much the same way. It is similar to shamanic journey work, but in precisely what ways I am not sure, as the access and rules are different. I mean to dig into this with Jade Grigori, the Mongolian American shaman I call friend. But the imaginal and shamanic realms share the notion held staunchly by their practitioners that they are real. That is, their terrain, their inhabitants and their rules exist independent of us and our best efforts to control them.

Imaginal art is not, principally, a fanciful way for accessing the artist’s subconscious content nor for outpicturing our private wishes and fantasies, although many skeptics see it this way. This skepticism is understandable (and I have, and sometimes still do, share it), because we are embedded in a rationalist worldview, a worldview that I believe is responsible for a deep epidemic of loneliness in our world today. I believe we stand at the brink of the cathartic and maybe chaotic process needed for reintegrating the imaginal with the rational, and that this is one part of the eco-social crisis we face as a global society. I am borrowing the term “eco-social crisis” from my friend and colleague, Katie Teague. And I am buoyed by and rooted in the work about these times that Richard Tarnas and others have brought forth in powerful and moving ways. Richard Tarnas’ Cosmos and Psyche is a must read if you’re interested at all in any of these ideas.

Defending imaginal art is not to say that we are all crystal clear mirrors. Not all of us create imaginal works of real depth and clarity. I do believe that anyone can access the imaginal realms, and this is why I created the Imaginal Journey with Nature (in 7 Easy Steps!). But going that step further to bring forth great works of broader significance for humanity seems to require something more. Genius? Talent? Persistence and devotion? Some or all of these, surely. Which points to another dimension of imaginal work: that its power lies in both its effectiveness, the validity of its revealed truths, and in the resonant chord it strikes with the reader or audience.

So, we who aspire to imaginal creation have work to do to polish the mirror, to get out of our own way so that our imaginal offerings can come forth without interference from our own personal baggage. There is also a place in imaginal creativity for intellectual rigor, as both Tolkein and Jung exercised. We must heat and forge it, hammer out its flaws, test it for weaknesses. This balance of inspiration and discipline takes time to develop for many of us mystical creatives, but it makes the difference between dabblings in a journal and great works of enduring meaning. Finally, we must develop and hone the skills needed. For me, this has come in writing, both as a received gift (the writing of my memoir which I describe in the article About Aran was such a gift), but also in years of ongoing practice to improve my writing skills, and it’s a process that is still ongoing. For another, say the theoretical scientist or musical composer, the skills would be those of their discipline.

Mainstream psychology and psychiatry have yet to embrace any of these ideas, but creatives, mystics, and psychonauts have stampeded toward them because they feel like home. Even though I hid for years, shy to publicly embrace my identity as both a mystic and a creative thinker, I feel quite at home here too. And I’m okay with mainstream resistance to these ideas. I am content to wait in the field of unity for rational science to meet us here. I am sure they will come bearing gifts–the fruits of their research, the scientific proofs, and perhaps the rational explanations for the power of this mystery.

Which brings us to my intention for this phase of the project, and my guide Aran’s hints about what I am “here to do,” (which he referred to in the postscript to the Sirius’ Gift for the New Year post). My intention has never been primarily creative, as it was for Tolkein. Instead, I’ve always sought truth. The mission to improve the maps we use for healing and fulfillment rests inside of that larger intention. But I think that I have actually been dithering at the threshold of a whole new kind of endeavor. It is now a full three weeks since he dropped that juicy portent into my lap, smiling like a cat, which he has never done in all the years I’ve sought purpose and meaning and finally surrendered to the idea I might never find anything other than purely personal and private life purposes. And yet, promise it he did, and I sense him waiting a tad impatiently for me to begin, while I have been lingering–like a cat–in the doorway.

Weeks ago, when I opened my mind to his hint, an impression leapt forward that I am meant to do visionary, and perhaps even prophetic work. I have wondered if this means I should be predicting things, as both a demonstration of the imaginal and as an outlet for much-needed information. The idea scares me a little, but I am determined to put this method through its paces more rigorously, and to test it against reality, not simply to draw on it as an aesthetic complement to my philosophical inquiries.

For now, I seem to have arrived quite unexpectedly at an understanding about the imaginal that I really like. It resolves my struggle with identifying just what particular territory or “place” we might be accessing, be it the etheric or noetic or shamanic realms. I see the imaginal process as a creative access to higher orders of reality, orders of reality which, in an infinitely expanding universe, must continue to expand out in ever widening spheres. These higher orders of reality can be thought of from a theoretical scientific perspective as higher dimensions or unknown areas of understanding about the physical universe. They can be seen from an esoteric, a shamanic, or artistic perspective, or any area which is unknown and theoretically unknowable at the present time.

And so the imaginal is a stance and an art (and for me a discipline, since I’m wired up that way) which is not bound to a particular location or type of question, just as the artist is not bound to a particular medium or subject matter. Perhaps there is a place called the imaginal realm, where all imaginal works can be found–a great confluence of intersecting realities, creative works, and artists, like a massive art studio. If so it would be a truly stupendous, wild and magical, dangerous and haunting and brilliant place indeed, as Tolkein described the realm of faerie: “The Land of Fairy Story is wide and deep and high […] its seas are shoreless and its stars uncounted, its beauty an enchantment and its peril ever-present; both joy and sorrow are poignant as a sword.”[8] For now, I am focusing on the imaginal as a method which holds potentials for revelation, and thus lends itself to grappling with mysteries. I look forward to these revelations in the coming months and years.

Research Notes

When I started this post, I did some homework. I looked up the definitions of the word “imaginal,” and followed the clues. And I took notes from Becca Tarnas’ work and looked at other writers. But I realized that part of what I’m doing is hammering out my own direct knowing and experience, and so I reserved these results for last, as a collection of parting thoughts.

Many dictionaries stop with the rather unhelpful and unimaginative definition, “of or relating to an image,” along with the even more cryptic, “of, relating to, or resembling an imago” [1] which turns out to be an entomology term referring to an adult insect post-metamorphosis! Occasionally, the psychological meaning of imago is noted as in, “an often idealized image of a person, usually a parent, formed in childhood and persisting unconsciously in adulthood.” [2] This rather dated psychological concept was later developed by Jung into his theory of archetypes [3][4]. The whole evolution of Jung’s thoughts on the matter of archetypes is actually a bit controversial. [5] Nonetheless, it does bring us back to archetypes, albeit by way of an old-fashioned version of them in the idealized image of the parent.

I liked what Cynthia Bourgeault had to say, although I’ve since exploded some of the notions a bit. In a 2018 blog post (she has since written a book on the topic), she wrote, “In traditional metaphysical language, it is the realm separating the denser corporeality of our earth plane from the progressively finer causalities which lie “above” us in the noetic and logoic realms. Put more simply, it separates the visible world from realms invisible but still perceivable through the eye of the heart. […] The imaginal realm is a meeting ground, a place of active exchange between two bandwidths of reality.” [6]

Finally, of course, I looked at Becca Tarnas. She has spoken about the imaginal in many ways, but says this in her recently published book, Journey to the Imaginal Realm: A Reader’s Guide to J. R. R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings:

Faerie, or the imaginal realm, is a domain that does not exist in a physical location, but that does not mean it is a place that does not exist at all, or is only made up or unreal. When you close your eyes, or when you read a story, images naturally arise. Where do these images come from? They exist in the imaginal realm, and we access them through the faculty of the imagination. Sometimes these images are fleeting, blurry, or ephemeral, and they are hard to grasp. But sometimes they can be fully immersive, what some call visions or visionary experience. We can even actively participate in them if we cultivate the practice or the discipline. This is what C. G. Jung called “active imagination”: a meditation with images that arise from the unconscious. [7]

Becca Tarnas, pp. xiv-xv

That’s as far as I got on the research, and then I came to my own conclusions. I’m going to be working with the imaginal in ways that are probably going to push my comfort zone a little. The main thing I’m going to be trying to do is really testing in some ways and challenging myself to offer something in the way of proof. It won’t all be about proof, but I don’t want to hide in my creativity. So stay tuned for that!

References

- imaginal. (n.d.) Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014. (1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014). Retrieved January 27 2022 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/imaginal

- imaginal. (n.d.) American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. (2011). Retrieved January 27 2022 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/imaginal.

- Ducret, Antoine “Imago .” International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. . Retrieved January 24, 2022 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/psychology/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/imago.

- imago. Oxford Reference. Retrieved 28 Jan. 2022, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095958223.

- Jungian archetypes. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 05:37, January 28, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jungian_archetypes&oldid=1067232376

- Bourgeault, C. (2018, November 13). Introducing the Imaginal [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://cynthiabourgeault.org/2018/11/13/introducing-the-imaginal/.

- Tarnas, B. (2019). Journey to the Imaginal Realm: A Reader’s Guide to J. R. R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings, pp. xiv-xv. Ingram Spark.

- Tarnas, B. (2019). p. xiv.