Photo by David Hablützel from Pexels

Audio

Or listen wherever your get your podcasts

A few years ago, maybe ten, I discovered that I can get bees and wasps to move their colonies out of high traffic areas by asking. I have no idea if this is a special talent or just something that no one ever tries to do. After all, most people view them as pests at best, dire danger at worst. I don’t think my successes have been a coincidence. I’ve had too many miraculous evacuations. So I thought I’d share my method in case anyone else wants to try it. I’d love to know if others can get it to work. And of course, my ultimate goal is to foster a spirit of collaboration with the non-human intelligences of nature and to seek peaceful outcomes wherever possible.

The discovery started with a tidbit I heard from Spikenard Honeybee Sanctuary here in Floyd, Virginia. At the time, I lived in an apartment in town and got a report from someone who’d taken a tour at the santuary. The tidbit was about formic acid. According to Gunther Hauk, co-founder of the sanctuary, all stinging insects including bees, wasps, hornets and also ants, excrete microscopic droplets of formic acid as they move about the environment. Apparently, this substance plays a critical role in the life cycles of most (or all?) biomes. Without these tiny droplets spread regularly throughout the environment, the ecosystems would fail! I found that information dazzling and humbling.

Spikenard offers a three-part recording around this teaching on their website: Formic Acid: The Gift of the Stinging Insects.

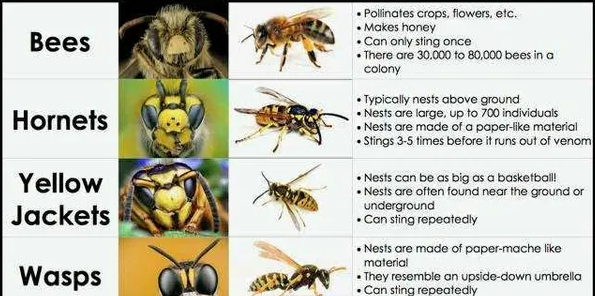

We wonder, “What good are these creatures?” Especially with pests like hornets and wasps which don’t even give us honey, it can seem like all they do is sting! But in fact, they’re helping to knit together the web of life. The crisis of colony collapse among honeybees has raised awareness of the importance of pollinators to the entire human food chain. I’ve heard worst case scenarios predicting worldwide famine within a year of a total collapse. But it was revolutionary to realize we have reason to thank all the stinging flying insects, creatures that most people would just assume bomb with a can of Raid!

The first time I successfully got a colony of “bees”–I’m sure they were some variety of wasp–to move, I’d just learned about formic acid when a friend complained that some bees had made a nest in the vinyl siding right near the formal front door of their house. The colony was pretty entrenched by the time of our conversation, vigorous and frightening enough to drive people to use the side door. She was going to have to call an exterminator. I begged her to reconsider, relaying what I’d learned about the formic acid. In a flash of inspiration, I suggested we try a meditation to see if we could ask the bees to move. Why I thought it would work, I have no idea. I wasn’t going to be able to go out in person, but even if I had, I don’t speak hornet. Still, it seemed better than doing nothing. So we did a meditation/prayer over the phone together. I gave the bees a weeklong deadline to move, which she’d agreed to honor. A week later, to my shock, the bees were gone!

After that, I tried it every time a nest was in danger of fumigation due to being dangerously located. I tried with different varieties of hornets and wasps in different kinds of locations: inside of a ladder that had been stored outside for a few years (you know those hollow aluminum ladders?), in outbuildings, in eaves, in walls. Each time the homeowner was planning to spray, I intervened, set a deadline, and by the time the homeowner went to execute their plan, the bees were gone. I should emphasize that I have not done this with actual honeybees. I can’t imagine asking an active honeybee hive to move. Seems like such a waste with all that honey. But I’ve done it with different people, across different timelines, and in different conditions.

The most intense one, which I didn’t actually expect to work, took a bit longer, more than a month. A friend had a shed building in which a very aggressive type of hornet had built a giant nest inside the main room in the far corner diagonally opposite the door. It was one of those big paper nests, and the hornets were constantly bombing in and out through the door all day long. You’d step through the doorway and have to duck. Very intense. She was a pacifist and green all the way, but couldn’t use this important outbuilding and was considering having someone come spray it for her while she was out of town. I offered to try to get them to leave. She was skeptical but dragging her feet because she hated using pesticides. She left me to it, declining to participate, but postponed taking action on the fumigation, and then went out of town. When she got home, she called me up. The hornets were completely gone.

My favorite example happened at the old mountain cabin my family owns in Nantahala, North Carolina. It’s an old 1930’s cabin where we sometimes spend a week or two during the summer. It’s got one of those wooden-framed screen doors that bangs when you let it shut behind you. I love the bang. They’ve since put a piston hinge on it (boo). Anyway, one summer we arrived to discover a bees nest in the walls right near the door. If you let the door bang behind you, it would disturb them and they’d fly out around you. We had to remember to gently shut the door, but would sometimes forget. On the last day, as we packed to leave, we forgot quite often and the bees were very stirred up. Then my mom got stung, and the guys decided that was it. They decided to ask my Uncle Gary who lived nearby to spray the bees next time he got a chance.

“Let me try first!” I said, and explained my method. My family is used to the occasional flight of fancy (and more!) from me, so they humored me. We asked my uncle to spray the bees but to wait at least a week before doing it. I fretted all the way home–urging them to find a place in the forest to live, worried they wouldn’t be able to do it in time because I thought they were actual honeybees and might be in the process of creating honey and the whole nine yards. When we checked in with Gary a few weeks later, he said that there were no bees when he went up to check it out. We’ve never since had a problem with bees in that house (though I’ve been lax about the gentle hornets nesting in the attic on the sunny side of the house because they don’t bother us). I think this was my favorite example because I had so many witnesses!

I have had zero success with mammals and birds. So far, insects and especially highly organized hive insects, have been the most responsive. But spiders too, actually. I hope more people will try innovative ways to deal with “pests.” Toward that end, here is my method for relocating wasps, hornets, and bees. Besides the experimental value, this is a far easier, toxin-free and cost-free way to deal with a potentially dangerous situation.

How to Relocate Bees, Wasps, and Hornets

- Educate yourself about their benefits. I believe this is one of the secret ingredients, together with whatever sincere appreciation or love you can find for these creatures.

- Assess the situation. Where is the nest located? What kind of bees, wasps, or hornets are they? Are there people at risk of bee sting who have allergies? Is there a construction project planned that will disturb an existing nest? What are the people who live near there planning to do about it? Is there a timeline? Are there other limits or situational constraints? If you can’t visit the site yourself, then it’s best if someone who has visited in person can be present for the actual communication (beginning in Step 4).

- Come up with a reasonable timeline. I’ve found that most hives can, if pressed, move within a week. Get the people involved to agree to a specific deadline and any other conditions. It’s important that these agreements be honored. Undertaking this kind of negotiation and then betraying the agreement is a terrible way to destroy trust.

- Choose a time and space for the communication. You will do this as a kind of group prayer or guided visualization, with eyes closed and a quiet and thoughtful attitude. I used to believe that the owner of the property should be involved, but that actually hasn’t been necessary. But anyone who wants to be involved, can be involved and you can do this as a group. You can gather over the phone or in person, onsite near the hive or at a distance.

- Quiet your mind and reach out with your imagination. Use your breath or your intent to quiet your mind and close your eyes. If you are working with a group of folks, go ahead and guide them verbally. You may feel awkward at times, but it doesn’t seem to make a huge difference to the bees. In your mind’s eye, seek out the location of the hive, and seek out the minds of the bees. Guide your group in this.

- Speak your gratitude and appreciation to the bees. After all, you’re going to the effort because you don’t want to kill them! Tell them that. The more heartfelt the better. This is what I often say, but modify this so it’s honest: “We love you, we know how important you are to all of the forms of life around you, we want you to thrive in balance with the rest of life.” Speak these outloud for your group. Try to hold the bees in your mind’s eye as you do. Notice if you feel a pulse of response or recognition from them.

- Now explain the problem to the bees. Just present the situation to them. Like, “You’ve built a nest right next to the front door of the house, and people going in and out risk getting stung. There are people who come over who are allergic and could die. This isn’t going to work longterm. It’s a bad place to build your nest and puts you in danger too. They’ve decided to call the exterminator! I don’t want that to happen.” Being straight about what the problem is can be a whole piece of work in and of itself, because sometimes it’s more of an annoyance or convenience factor rather than any dire urgency.

- Next, offer a solution. If you already have a better location in mind, you can suggest that to them and visualize them moving toward it over and over again. But honestly, I don’t know that much about what works for them, so I usually limit my suggestions to the places where I don’t want them to build. For example, “There’s miles of forest out there. Can you find another place to build your nest that’s away from hiking trails?” Or, “The old shed that’s falling down should be safe for a few years as long as you know that one day we’ll have to take it down.” Be reasonable, pragmatic, and friendly.

- Agree on a deadline. Sometimes that deadline is forced upon you by the other folks involved. Make sure you’ve done Step 3 before you start this process. Sometimes the folks involved don’t have a hard deadline but the wasps or hornets will volunteer one. This might be more advanced in the practice, but it just feels like getting a clear impression from the bees. For example, there were two kinds of wasps in the farmhouse bathroom I recently worked on renovating. The brown ones eagerly and willingly were preparing to leave even as I began speaking to them. The more aggressive yellow striped ones (they told me they’re hunters) took a longer time to talk with and finally agreed on a one month timeline to scout and locate someplace better that met all my requirements.

- Consider your leverage. A threat of extermination is obviously great leverage and gets the ball rolling quickly. But sometimes, as with the owner of the farmhouse, there’s no intent to kill or poison the bees. There may not even be any urgent need for their removal. We have wasps in the eaves of our house that I’ve never had the heart to ask to leave because they’re pretty mild and we’re not allergic. But recently I got stung, so I asked them to leave. They were very blase about it. I think they knew I wasn’t going to force the issue. So I told them how much I wanted to create a beautiful harmony with wasps in general, how I wanted to show a better way, and to preserve them. They perked right up and said, “Sure! We can move down into the woods.” Remarkably, when I suggested a certain section of the wood pile, Michael found them nesting right there several months later. I also found that my plants under the eaves were riddled with holes (the wasps had been keeping the munching caterpillars under control). And then Michael forgot his promise not to take wood from that section of the wood pile for a year and we had all these dead and dying wasps indoors the next winter. I felt terrible! So the following year I invited them back into the eaves.

Maybe this is a portable skill, maybe it isn’t. Maybe I have psychic abilities that allow me to communicate with bees and wasps and hornets. Maybe these capacities are rather common. I’d love to find out. I also think we have been woefully ignorant about how important our non-human partners are. I’d love for other people to begin to explore and discover new borders and landscapes of thought, feeling, and being.